For years, we have proudly conducted industry research in collaboration with private club association across the globe, including the Club Management Association of Canada (CMAC), National Club Association (NCA) and the Club Management Association of America (CMAA). Regardless of the survey, one notion has consistently remained: analyzing research data to derive insight is complex.

The primary purpose of our most recent survey initiative in collaboration with CMAA, 2022 A Club Leader’s Perspective: Emerging Trends & Challenges (CLP) is “To explore the perspectives club leaders have about the industry and their club’s performance.”

The CLP research is not intended to provide comprehensive benchmarking for use in evaluating individual club performance, but rather to provide an overview of trends in the industry from the perspective of club leaders. And these perspectives are derived from a diverse cross-section of clubs, including a variety of club types, in different markets and with different business models. For instance, almost 20% of the 2022 CLP survey respondents represented for-profit clubs, which at times structure their business models differently than non-profit, member-owned clubs.

Why is this important?

Our firm routinely conducts comprehensive benchmarking and operational reviews for clients, and while we recognize the value of self-reported data, we do not rely on survey responses from any of our trends surveys or other industry surveys. For benchmarking to be effective, it requires in-depth financial analysis at the trial balance level, understanding of the key physical characteristics of a club’s facilities, understanding of the club’s operating hours and service offerings, and understanding of staffing, including head counts, full-time equivalents, salaries, wages, and benefits, with comparisons only drawn to truly comparable clubs. There is rigorous analysis required in conducting benchmarking.

Comparisons of aggregated data without detailed analysis and without context provided to club leaders by experienced professionals with respect to what the results mean to their club given their vision for the club, their members’ expectations and their unique market circumstances are not benchmarks and should not be relied upon to make strategic decisions.

Our work with club industry associations is incredibly illuminating and we are committed to continuing conversations with club leaders now and in the future. We fully support the use of perspective research to ignite discussions and to help highlight important topics of focus. After receiving a few inquiries related to 2021 Food & Beverage (F&B) performance as reported by the CLP Report survey respondents, we felt that additional context and clarity on this topic would be valuable.

Before delving into the F&B survey data in the CLP Report, we want to reaffirm that our research team conducted extensive analysis of the survey results, and the results reported in the report reflect the responses received. Nonetheless, readers will note from the scatter plot of responses provided in the report, that there are assumed outliers that we classify as highly likely to be inaccurately reported data by some survey respondents. While certain results reported by club leaders did not appear to be appropriate, we did not adjust the responses and reported the results as provided. The use of a median in the analysis is important given the likelihood of potentially inaccurately reported data in surveys of this nature. That said, given feedback we have received, we conducted further analysis into the survey data and developed additional context for our readers.

Digging Deeper into the Survey Data

The raw survey responses, as reported, produced a median total annual profit on F&B of approximately $70k, equating to an implied median profit margin of 7% in 2021, with 64% of respondents indicating that their club generated a profit.

Further consideration and applying both our best discretion and professional judgement to the data, we estimate that approximately 10% of the respondent data was likely not entered appropriately, either due to a possible misunderstanding of the question or a transcription error.

If we were to exclude these data points from the analysis, the median total annual profit on F&B is closer to break-even, with just over 50% reporting a profit. It is important to note that this does not consider potential improperly reported extraordinary loss data points, which is more difficult to ascertain and appears to occur less frequently in the data.

Food and Beverage Profitability Trends

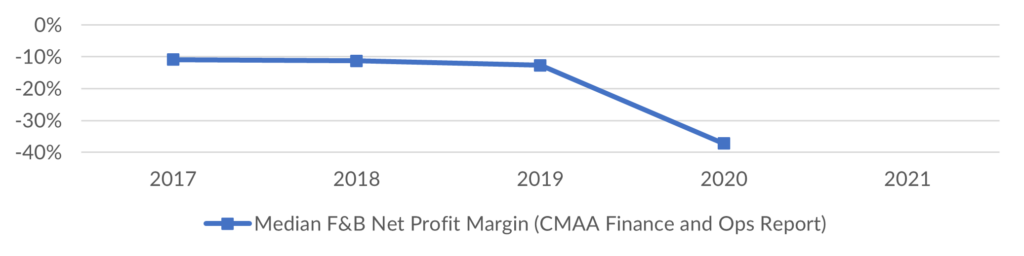

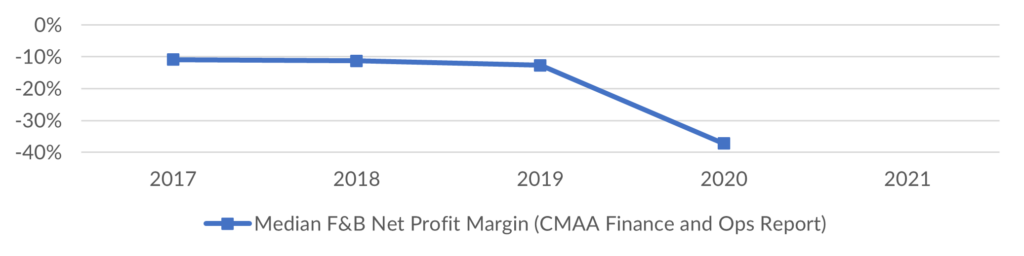

The CMAA Finance and Operations Study provides a good frame of reference for food and beverage profitability:

- CMAA Finance and Operations Survey Trend – Food and beverage net profit/loss held a consistent (flat) trend from 2017-2019, with the average performance being a net loss ranging between 10-13% of revenue. This sample of respondents is more heavily represented by non-profit club structures as compared to the CLP survey respondent profile of clubs. In 2020, the pandemic driven challenges drove the median net loss on revenue to 37%. 2021 results will be included in the release of the 2022 Finance and Operations report.

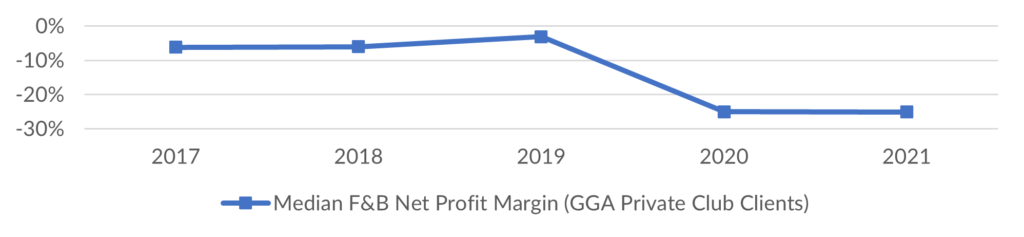

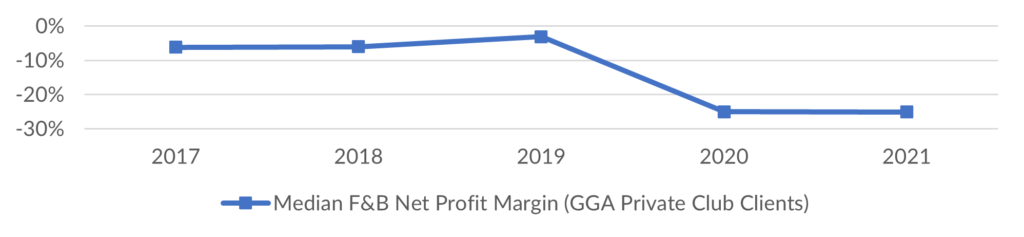

When compared to our internal GGA Partners database of historical trial balance level client financial results and 2022 budgets, which includes both for-profit and non-profit clubs:

- GGA Database Trend – Net profit/loss held a consistent (flat) trend from 2017-2019, with the median performance being a net loss ranging from 3-6% of total revenue. In 2020, the pandemic driven challenges drove the median net loss on revenue to 25%. In 2021, the median net loss remained consistent at 25% of total revenue. We expect performance to continue to improve in 2022 and generate a median net loss in the range of 8-15% of revenue, based on our review of 2022 budgeted income statements among our client base thus far.

Purpose at the Core of Strategic Decisions

“Is it possible to make money on F&B? Or are we better off subsidizing the operation to improve the experience for members?” For years, our clients have asked these questions. Food and beverage operations at private clubs create a challenging business model by nature and should not be compared to the restaurant operation down the street (even though members often make this comparison). However, to say definitively that your operation should not make a profit is also ill-advised. Many of GGA’s clients generate a profit within their F&B operations, however, this is a strategic decision (dependent on several market factors) and more prominent within for-profit structures.

Your budgetary philosophy on F&B is a strategic decision for your club and should be based on what members want, and what the market allows from a price elasticity and competitive positioning perspective. Our member survey work frequently demonstrates how important and impactful F&B operations at private clubs are. Often, there is a strong statistical correlation between members’ satisfaction with F&B and overall satisfaction with the club. As a result, when a non-profit club’s annual dues and overall business model can support an expanded food and beverage offering, elevated service levels and discounted menu pricing, many clubs make the strategic decision to manage their food and beverage operation to a loss, in favor of an elevated member experience and overall satisfaction with being a member.

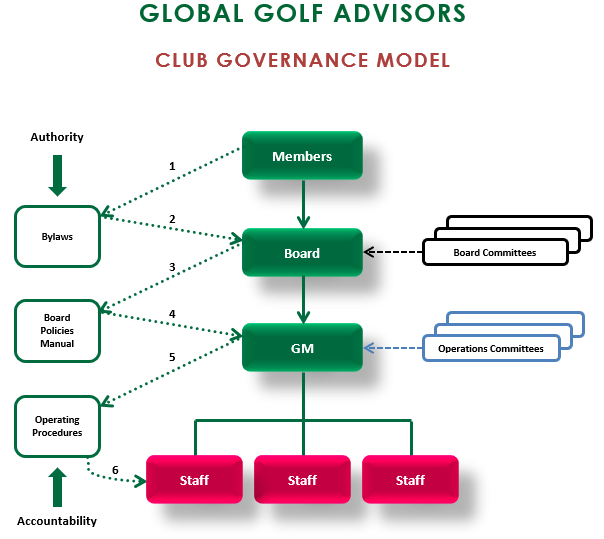

While there is considerable skill required to execute a food and beverage business plan, the formulation of that business plan is largely a mathematical exercise that can be viewed as a sum of the parts. In a non-profit, member-owned club, the ‘parts’ are what the members, through the board of directors and as part of a well-formulated strategy, determine and communicate to management. These ‘parts’ include:

-

- The number of food and beverage outlets to operate.

- The hours of operation for those outlets.

- The level of service required and thus the staff requirements during operating hours.

- The quality of the products procured and offered for sale.

- The pricing strategy for how the club prices its food and beverage products it sells.

- The number of events the club plans to host.

- The source of events, whether member, member-sponsored or external third-party events, and pricing strategy deployed.

For those that may have read the F&B related CLP survey results with concern, we strongly recommend you ensure there is a comprehensive strategic plan in place at your club. This requires a clear understanding of the food and beverage experience that club members desire, and the operational and capital costs required to deliver on those expectations. The decision must then be made to determine how (or if) the club can deliver on the F&B experience in a manner that is financially sustainable. The feedback we received on the F&B results in the CLP research report underscore the necessity for strategic planning that incorporates financial forecasts and key financial targets, through which the board of directors guides management to operate, along with the importance of succession planning for board members, ensuring a knowledgeable and informed leadership group.

For any questions or for assistance in benchmarking your operation and setting the most impactful strategy for your club, please contract us at info@ggapartners.com.

Access the 2022 A Club Leader’s Perspective: Emerging Trends & Challenges report.