There’s an inherent quirk with how members view authority. Individuals elected for board service are often popular, though not necessarily qualified, and the qualified are not always popular. Who’s to set the balance?

GGA Partners’ Henry DeLozier spells out the importance and role of the nominating committee; who they are, who they should nominate, and how to make sure they are a trusted agent of members at large.

In most private clubs, it is the nominating committee that sets the future of the club. The proverbial queen- or king-maker, the nominating committee profoundly impacts the tone and tenor of club governance.

In clubs using an uncontested election model (members voting for a selected slate of candidates) for board service, it is the nominating committee which selects the club’s future leaders. In clubs with a contested election model (multiple members run for open board seats and are selected by a popular vote of club members) the nominating committee either proves itself to be a trustworthy and balanced agent of the members or a group of members out of touch with the preferences and priorities of their fellow members.

In either case, nominating committee members should be well-known members of the club recognized for their integrity, character, and good judgement.

Whether your club is fortunate to possess a rich pool of individuals who meet this criterion or not, there should always be a charter in place to help guide the selection process and define the role of the committee once in post.

What other steps can you take to select and shape an effective nominating committee?

Define the limits to authority

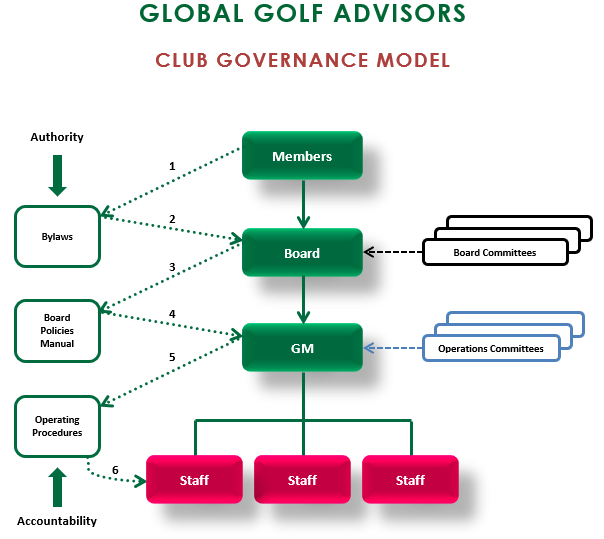

The authority of the nominating committee should be defined within the club’s bylaws and/or Board Policies Manual, with the nominating committee charter aligning with these two governing documents.

Nominating committees should not be permanent. Clearly established guidelines must be a part of the charter for the term of service. Typical terms for a nominating committee should range from three to six years – dependent upon the term of service for board members.

On an as-needed basis, nominating committees may evaluate the board’s term limits and modify them if needed for board efficiency or to accommodate the changing size of the board.

Set the selection criteria

The charter should provide the committee guidance concerning the qualifications and/or capabilities required of future board members. For example, most clubs benefit from members with legal, banking / finance, insurance, and public accounting backgrounds.

It is desirable to nominate members whose interests differ to provide balanced and impartial governance. For example, a board made up of all avid golfers can be perceived to be out of balance by members with interests other than golf. Avoid nominating members who represent “constituencies” of like-minded members. Each board nominee should represent and seek to understand all members’ viewpoints.

Selection criteria should be definitive concerning conflicts of interest – whether real or perceived – and all other potential factors that could serve to undermine the credibility of the committee and its nominees.

Ensure candidates bring value to the table

A growing number of clubs have introduced specific requirements of board members, and this is something the nominating committee should focus on when defining methods of recruiting prospective board members. Where they are relevant and a potential source of value to your club, these should feature in the charter.

For instance, you can stipulate that a prospective board member has successfully recruited a member of the club, or you could set policies for the giving or fundraising expectations of board members. Specific, tangible value delivered back to the club which symbolizes a ‘lead from the front’ mentality, setting the tone and an example for members at large.

Not only will this help send the right message, it also ensures each member of the board is accountable, bringing something beyond their invaluable rich experience, guidance and ideas to the table.

The role and responsibilities of the nominating committee are profound and great care and transparency must be given to populating the committee with the club’s most respected members.