This article continues a series of communications from GGA Partners to help private club leaders address challenges confronting their businesses and their employees as a result of the global health crisis. Today, Henry DeLozier offers several examples of the right things to do if you are a crisis leader.

Excellent leadership is a mixture of many important ingredients and information – access to it and knowing how to use it – is critical to the mixture. Smart leaders are using time during the novel coronavirus outbreak to sort through many sources of information to choose the most relevant and insightful information sources available to them.

During this pandemic, leadership qualities are being revealed in no uncertain terms. Those who have reliable information and can explain circumstances succinctly, consistently, and timely are viewed as “crisis leaders”. At GGA Partners, we consider someone to be a “crisis leader” when they are able to do the right things right.

Following are several examples of the right things to do, if you are a crisis leader:

Understand the significance of trustworthy leadership.

Achieving trustworthiness requires having reliable and current information, maintaining an on-going dialogue with those relying on you, and being truthful in your dealings. If the news is bad, trusted leaders are able to convey the combination of truthful expectations or projections in an empathetic manner.

After England suffered the fall of Dunkirk, Winston Churchill described “a colossal military failure” when reporting to the House of Commons at Parliament. He did not mince words and aligned accountability – his own – with the authority given him. People trust those who can step up in tough times.

Manage information aggressively.

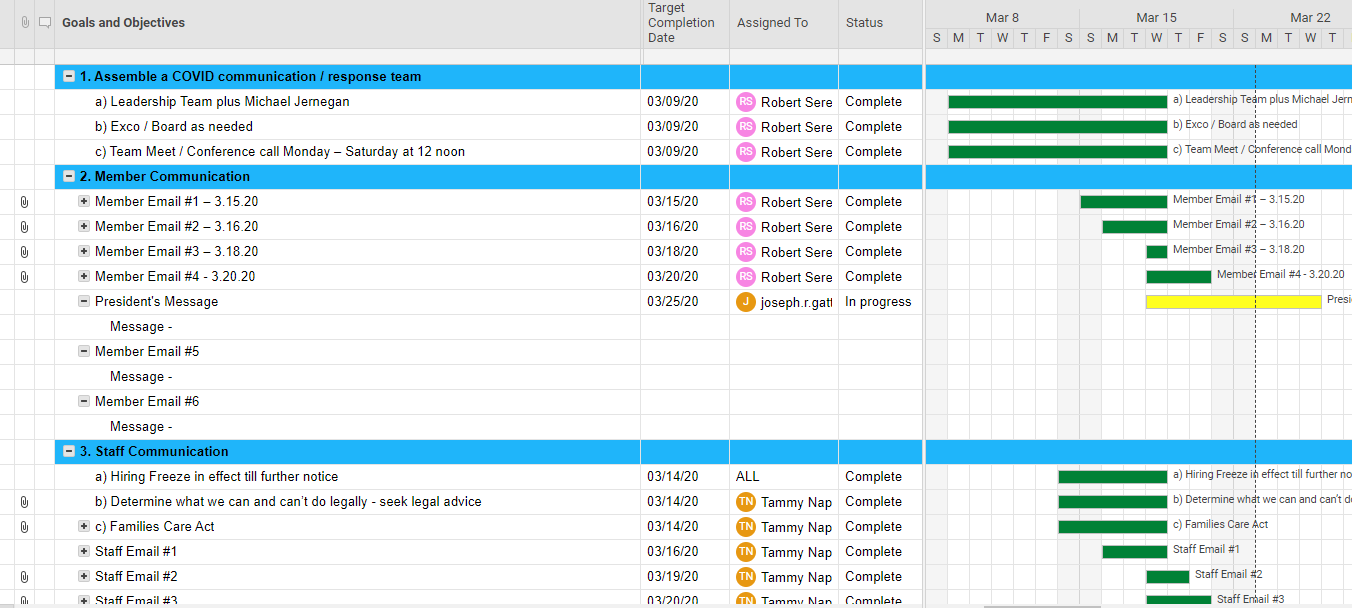

Keep your stakeholder groups of members, employees, suppliers, and extended business partners – like bankers and insurance carriers – well-informed. It is essential to be inclusive, informative, and accurate. Do not make any incorrect statements.

Club leaders serve many stakeholder groups which often have different needs and priorities. Evaluate your stakeholder groups and refine communications which decisively and clearly address the expectations and needs of each group.

Express optimism.

US President John Kennedy focused his countrymen on a goal of putting a man on the moon in May, 1961, when he told the US Congress, “This nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth.” At the time, this was not a popular idea as 58% of American’s polled were opposed to the idea. And yet, in July of 1969, Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins fulfilled the slain President’s goal.

Churchill’s ability to deliver dreadful news, like the fall of Dunkirk and Singapore, was supported by his bull-doggedness in telling the British people that they would “never surrender” as he pointed out that Britain’s far-flung empire and the New World powers would come to the rescue, as they did. Bitter truth was supported by an optimistic outcome.

Be present.

Maintain regular – if even predictable – contact with your stakeholder groups. Address their concerns in the context of updated information. See that your information updates are available using multiple media – such as email, social media, direct mail, and conference calls – and be willing to repeat certain key bits of information for the sake of emphasis.

Communicate your plans – and act on them.

Your members want information, to be sure. Even more importantly, they want confidence that their club is in steady hands. They want to see evidence – action more so than talk – that the club is taking measured steps and addressing the key strategic issues without distraction with petty short-term matters. This capability requires a reliable game plan.

In her 2018 book entitled Leadership in Turbulent Times Pulitzer Prize winning historian, Doris Kearns Goodwin, cites several specific lessons that can be drawn from Franklin Roosevelt’s first term in leading America from the depths of the Great Depression. First and foremost, indicate that there is a center-point of leadership and direction. Roosevelt made clear his understanding that he was chosen to lead. Then, came the Hundred Days and the New Deal…so there was a plan. Now, as for Roosevelt, planning must be very dynamic and agile.

Sound leadership is a matter of thoughtful and comprehensive planning. The clubs that will prosper after these difficult times are the clubs with a plan that is comprehensive in nature and not drafted in piece-meal fashion.

You can’t predict a crisis, but you can – and should – plan for one.

You can’t predict a crisis, but you can – and should – plan for one.

In times like these, the impulse is to act. To take decisive action in response to the enormous challenges the coronavirus has placed at our feet.

In times like these, the impulse is to act. To take decisive action in response to the enormous challenges the coronavirus has placed at our feet.

It’s easy to say and it’s been said so often that it should be hard for any leader to forget: In times of crisis, communication is key.

It’s easy to say and it’s been said so often that it should be hard for any leader to forget: In times of crisis, communication is key.